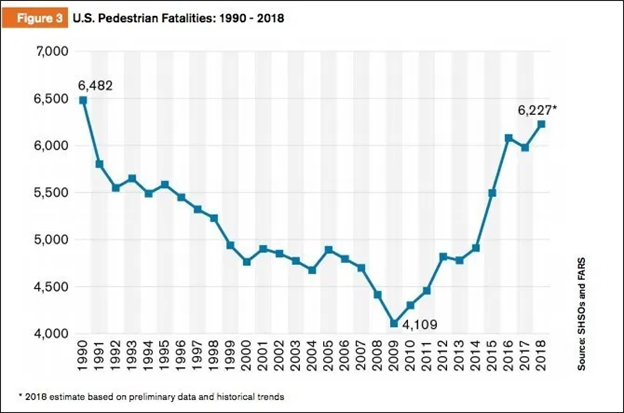

When focusing on intersection safety, it is important to consider all modes of transportation, including pedestrians, who are arguably the most vulnerable road user when crossing an intersection. In fact, according to a study by the Governor’s Highway Safety Association, in 2018 across the US there were 6,227 pedestrian fatalities along roadways, an increase of over 50% since 2009.

Improperly timed traffic signals can lead to potentially devastating outcomes, which is why Iteris and our traffic engineering consultants work with agencies to take special consideration of these vulnerable road users when timing intersections. In this blog, we will explore how pedestrian signals are timed and some important questions to consider when timing intersections.

How are pedestrian signals actually timed?

The Walk interval, which is represented by the walking man symbol, has the primary function of getting a pedestrian off the curb and on their way across the street. Its timing is based on the reaction time for a pedestrian to see that the Walk indication has come on, and to step to the curb and into the crosswalk. The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD), which provides standards and guidelines for all traffic control devices in the United States, recommends a minimum value of seven seconds. In most locations, the seven-second value works fine, however, some agencies will increase this value to 10 seconds where school crossing guards are present or if there are other similar circumstances that require a little added time. The Walk time can be significantly longer based upon other timing strategies related to the intersection’s operation.

The Pedestrian Change interval, represented by the flashing Don’t Walk or orange hand symbol, is intended to allow a pedestrian who has started their crossing on Walk to be able to cross the road before conflicting traffic is released. This time interval is based on the assumed walking speed of a pedestrian; the MUTCD recommends a value of 3.5 feet per second, with consideration of a lower value for locations with significant numbers of pedestrians who walk slower. As a safety factor, the MUTCD also requires at least a three-second buffer time between the end of the Pedestrian Change interval and the release of conflicting vehicles.

How fast do pedestrians usually walk?

Studies have shown pedestrian walking speeds ranging between 2.0 and 4.3 feet per second. Slower-walking pedestrians can typically include older pedestrians, people with disabilities, young children and people pushing a baby stroller or attending to young children. Therefore, traffic engineers also consider the usage of the crosswalk and the nature of the surrounding area.

Accounting for the most vulnerable road users

- Understanding the limitations of some pedestrians and their presence at an intersection helps to make signalized intersections safer for everyone, which is why we always consider whether the location of our intersections are near: pre-schools, kindergartens or elementary schools;

- retirement centers or medical complexes; or

- facilities that serve the disabled

How do we know when there are potential concerns?

Fortunately, there are cloud-based software tools available today that offer traffic engineers the appropriate data to monitor potential pedestrian conflicts and walk-time patterns. ClearGuide’s SPM module combined with Iteris’ Vantage Vector Hybrid detection sensor, for example provides agencies with the data necessary to understand how long pedestrians wait, when there are potential pedestrian conflicts and when pedestrians are still in the intersection after the flashing Don’t Walk interval. These data can be used to make impactful adjustments to improve intersection safety while maintaining efficient throughput along a corridor.

The Bottom Line

It is important to consider context when timing traffic signals, specifically understanding the demographics where the signal is located. Adjusting signal timing strategies to meet the local demographics can make intersections safer for all road users, and leveraging software tools will help you identify intersections that are most at-risk based on field data.

About the Author

Pete Yauch, P.E., PTOE, RSP2I is vice president at Iteris. Connect with Pete on LinkedIn.